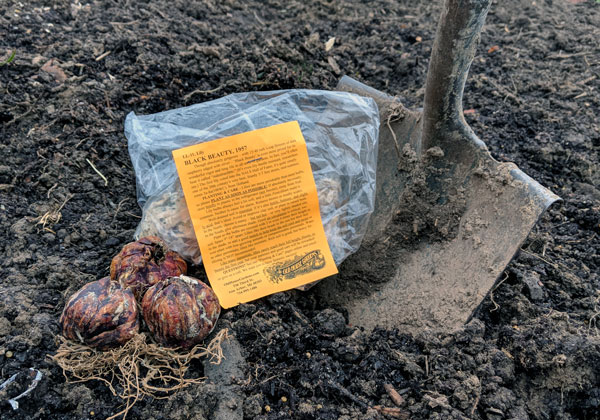

Workers repaving a street in Grand Rapids, Michigan, this past August were surprised by what they found buried under the layers of old asphalt – wooden paving bricks from over a century ago, many of which were still in perfect shape.

In his 1891 History of the City of Grand Rapids, Albert Baxter explains that “a change in Grand Rapids pavements from cobblestone to wood was made in 1874. The first wood pavements were made of blocks cut from four-inch pine planks set on end upon a gravel bed, . . . making a wood roadway six inches in depth.” Unfortunately the pine decayed after five or six years, so “the next advance was in the use of cedar blocks.” Cedar is naturally rot-resistant, and “the cedar block has proved much the more durable, and is the popular pavement to this day.”

I learned a lot more about the evolution of the city’s streets in Baxter’s book – and the early history of paving in your city was probably similar to it.

“Naturally the first wagon roads to the village,” he writes, followed “paths which the Indians had trod and were correspondingly crooked.” In 1835 the first right-angled streets were laid out and cleared but otherwise unimproved except for “little plank or log bridges across streams and mud holes.”

Further improvements “involved a vast amount of labor and expense.” Although Grand Rapids isn’t especially hilly, some high spots were cut down by as much as 40 feet and the resulting fill dirt used to raise low-lying streets by up to 15 feet – all without the help of mechanized equipment.

The next advance was paving, with Canal Street “macadamized” in 1847. This relatively new process involved layers of crushed stone that, with use, would bind into a solid surface. Unfortunately the mud under Canal Street proved to be too much for the macadam which was soon riddled with “mire holes.”

Next the city tried a few sections of wooden plank road, a “passably good pavement,” before turning to cobblestone in 1856. “Cobble stone well laid on a solid even bed is a good pavement, indefinitely durable,” Baxter writes, but it is “very noisy and hard upon the horses’ feet.”

“During the war period,” he continues, “not much progress was made in paving,” but starting in 1866 some streets were paved with “round stone” – which, as best as I can figure, consisted of smooth, uncrushed stones. (If you know more, please let me know.)

Wooden blocks came next, and “after this little if any stone pavement was laid except along street borders and gutters” – although Baxter does mention recent “experiments” with a brand-new paving material for sidewalks known as “artificial stone or concrete.”

If you’ve read this far, you might enjoy the entire Chapter 50 of Baxter’s History, “Village Roads and City Streets.” As you can probably tell, I found it fascinating.